A patient should undergo screening for pain during emergency department visits and on admission.

Each facility should have defined criteria to screen for, assess, and reassess a patient's pain. These criteria should be consistent with the patient's age, condition, and ability to understand. For example, a facility may designate a specific pain assessment tool as appropriate for use with cognitively impaired adults or for those who have an intellectual disability. When choosing a pain assessment tool for a patient, be sure to choose from the facility's selected tools. If one tool doesn't work, try another. After you've identified a tool that works for a patient, use it consistently unless the patient's situation changes (for example, the patient becomes comatose).

Examples of pain assessment tools for patients who are verbal and can self-report are numeric pain scales, the visual analog scale, the word-graphic rating scale, and the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale.

For patients who can't self-report, such as those who are nonverbal, have cognitive issues, or have an intellectual disability, pain assessment tools that may be helpful are the FLACC (face, legs, activity, cry, consolability) Scale, the Behavioral Pain Scale, and the Nonverbal Pain Assessment Tool.

For critically ill patients, intubated or nonintubated, the pain assessment tool that may be most helpful is the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool.

Remember that pain is subjective, and you should use pain assessment criteria to compare the patient's pain intensity at different times and help evaluate progress toward pain management goals.Don't use these criteria to compare one patient's pain level with another patient's pain level. Reassessment of pain at designated intervals according to the type of pain intervention (for example, oral, IV, or transdermal route) is necessary to evaluate progress toward pain management goals.

Equipment

Equipment

- Disinfectant pads

- Facility-approved pain assessment tool

- Pulse oximeter and probe

- Stethoscope

- Vital signs monitoring equipment

Preparation of Equipment

Preparation of Equipment

Inspect all equipment and supplies. If a product is expired, is defective, or has compromised integrity, remove it from patient use, label it as expired or defective, and report the expiration or defect as directed by your facility.

Implementation

Implementation

- Review the patient's medical record for information related to the patient's current clinical condition, past medical history, and pain management goals (when available).

- Review the patient's pain history, including previous use or abuse of analgesics, possible adverse effects associated with potential opioid tolerance or intolerance, and previous pain level (when available).

- Determine whether the patient takes any medications that may affect the perception of pain or the ability to communicate pain. Some medications, such as benzodiazepines, phenothiazine, and barbiturates, sedate the patient or reduce anxiety but don't provide analgesia.

- Gather and prepare the necessary equipment and supplies.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Confirm the patient's identity using at least two patient identifiers.

- Provide privacy.

- Raise the bed to waist level before providing care to prevent caregiver back strain.

- Ask the patient about pain. If the patient is experiencing pain, ask about the pain's character, quality, onset, location (and whether it radiates), duration, and frequency. Determine what exacerbates the pain and what relieves it. Determine whether the patient has a current pain management regimen and, if so, how it relates to the current level of pain. Findings from these assessments provide information about the patient's current pain level and provide a baseline for future assessments.

- Assess the patient's level of functioning, including the ability to participate in activities of daily living. Evaluating the patient's level of function is important because pain affects the degree of independence, level of need for caregivers, and overall quality of life.

- Assess which coping techniques have previously been successful to establish a guideline for future interventions.

- Assess for the presence of pain indicators, taking into consideration the patient's age and sleep patterns.

- Acute pain indicators include statements of pain, increased respiratory or heart rate, increased blood pressure, shallow respirations, decreased oxygen saturation level, diaphoresis, crying, moaning, restlessness, anxiety, irritability, guarding of a body part, and grimacing.

- Chronic pain indicators include disrupted sleep, changes in eating patterns, withdrawal from activities, and symptoms of depression.

- Screen for and assess the patient's pain using facility-defined criteria that are consistent with the patient's age, condition, and ability to understand. As directed, use a validated, appropriate facility-approved pain assessment tool. After you identify a tool that works well for the individual patient, use the same tool each time unless the patient's condition changes (for example, the patient becomes disoriented or unresponsive) to evaluate progress toward pain management goals.

|

EQUIPMENT PAIN SCALES |

|

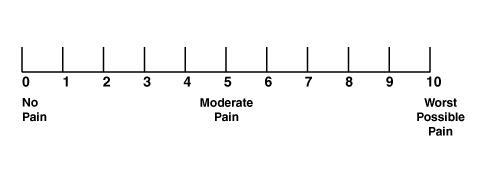

Various pain assessment tools exist. Be sure to choose a facility-approved tool that's appropriate for the patient's condition. Below are three common pain scales: a numeric pain scale, a visual analog scale, and the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale. Numeric Pain Scale A numeric pain scale, shown below, is a self-report tool. To use it, the patient must have a concept of numbers and their relationship to each other. The scale can be vertical or horizontal. The numbers range from 0 to 10, where 0 is no pain and 10 is the worst possible pain. The nurse should ask the patient to pick the number that corresponds to the pain level.

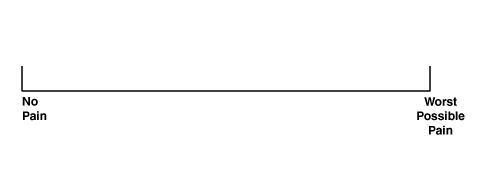

Visual Analog Scale A visual analog scale, shown below, is a self-report tool that consists of a straight line of a certain length (for example, 10 cm). One end is labeled "No Pain" and the other end is labeled "Worst Possible Pain." The patient marks a line at a place on the scale that best describes the pain. The nurse then measures the distance from the "No Pain" end to the mark that the patient made to determine the pain level. The nurse should document this measurement for later use to compare subsequent pain levels and evaluate the effectiveness of the pain management plan.

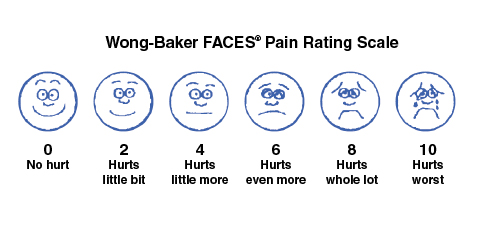

Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale A nurse may use the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale, shown below, with patients who have mild dementia or for those who can't understand a numeric pain scale. It's a self-report tool in which the patient points to the face that adequately illustrates pain intensity. Each face corresponds to a number on the scale. Explain to the patient what each face means before having the patient rate the pain. To use the FACES scale, explain to the patient that each face represents a person who feels happy because of having no pain or is sad because of having some or a lot of pain. Face 0 is very happy because nothing hurts. Face 2 hurts just a little bit. Face 4 hurts a little more. Face 6 hurts even more. Face 8 hurts a whole lot. Face 10 hurts as much as you can imagine, although you don't have to be crying to feel this bad. Ask the patient to choose the face that best describes how the patient is feeling.

© 1983 Wong-Baker FACES® Foundation, https://wongbakerfaces.org/. Used with permission. Originally published in Whaley & Wong’s Nursing Care of Infants and Children. © Elsevier Inc. |

- Perform a thorough physical examination that includes the painful area to help determine the etiology and pathophysiology of the pain.

- In collaboration with the multidisciplinary team, involve the patient in the pain management planning process. Provide education on pain management, treatment options, and the safe use of opioid and nonopioid medications when prescribed. Develop realistic expectations and measurable goals that the patient understands for the degree, duration, and reduction of pain. Discuss objectives to use to evaluate treatment progress (for example, relief of pain and improved physical and psychosocial function).

- Monitor closely if the patient is at high risk for adverse outcomes related to opioid treatment, if prescribed.

Clinical alert: When tapering opioids, monitor patients closely for signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal, such as restlessness, lacrimation, rhinorrhea, yawning, perspiration, chills, myalgia, mydriasis, irritability, anxiety, insomnia, backache, joint pain, weakness, abdominal cramps, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, increased blood pressure or heart rate, and increased respiratory rate. Such symptoms may indicate a need to taper more slowly. Also monitor for suicidal thoughts, use of other substances, or changes in mood.

Clinical alert: When tapering opioids, monitor patients closely for signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal, such as restlessness, lacrimation, rhinorrhea, yawning, perspiration, chills, myalgia, mydriasis, irritability, anxiety, insomnia, backache, joint pain, weakness, abdominal cramps, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, increased blood pressure or heart rate, and increased respiratory rate. Such symptoms may indicate a need to taper more slowly. Also monitor for suicidal thoughts, use of other substances, or changes in mood.

- Reassess and respond to the patient's pain by evaluating the response to treatment and progress toward pain management goals. Assess for adverse reactions and risk factors for adverse events that may result from treatment.

- Return the bed to the lowest position to prevent falls and maintain the patient's safety.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Clean and disinfect your stethoscope with a disinfectant pad to prevent the spread of infection.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Document the procedure.

Special Considerations

Special Considerations

- If the cause of acute pain is predictable, such as with surgery, inform the patient in advance about feelings that the patient may experience and the planned procedures for pain assessment and treatment. Doing so may help reduce stress.

- If your organization has an anatomic pain diagram, have the patient point to the location on the diagram that corresponds to the location of the pain.

- If a patient has limited verbal or cognitive skills, you can have the patient self-report by using a simple "yes" or "no" answer or by using a hand grasp or eye blink. Document why a self-report wasn't obtainable in the patient's medical record and those interventions you performed to investigate further.

- For a patient who can't self-report, such as a cognitively impaired or nonverbal patient, use a combination of assessment strategies, including an assessment tool such as the FLACC (face, legs, activity, cry, consolability) Scale, the Behavioral Pain Scale, or the Nonverbal Pain Assessment Tool; behavior interpretation; a pain estimate made by others, such as a family member or an unlicensed caregiver familiar with the patient; or even an analgesic trial to determine whether it produces a reduction in pain, as indicated by a change in behavior. For this population, using only one strategy doesn't sufficiently assess pain.

- A multidimensional pain assessment and treatment are necessary for chronic pain. Consultation with a pain specialist may be beneficial to a patient who experiences chronic pain.

- Use the same assessment tools for patients who are near the end of life as you would for the general population. Be sure to ask the patient to self-report the pain. Assess for potential sources of pain and observe for changes in the patient's behavior.Pain assessment tools that may be helpful for this population include the Multidimensional Objective Pain Assessment Tool and the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Tool.

Patient Teaching

Patient Teaching

Teach the patient and the family (if applicable) how to use an appropriate pain assessment tool and instruct them to use it before a painful event, when possible, to obtain a baseline for comparison. Select the tool based on the patient's cognitive level, the type of pain or the patient's medical condition, and the patient's ability to self-report. Make sure that the patient understands the tool; if not, introduce a different tool.

Inform the patient and the family about guidelines for pain assessment, including the frequency of reassessment. Make sure that the patient and the family know to notify the practitioner if they can't maintain the pain at or below the goal pain level.

Complications

Complications

Complications associated with untreated pain due to failure to perform pain assessments may include:

- multisystemic effects (such as tachycardia or bradycardia, hypertension, desaturation and bradypnea, hypercoagulability, and altered immune function)

- development of chronic disabling pain that can seriously impact the patient's functioning, quality of life, and wellbeing

- limited mobility

- increased physiologic stress

- increased risk of complications such as pneumonia and thromboembolism

- anxiety and agitation.

Documentation

Documentation

Documentation associated with pain assessment includes:

- initial assessment findings

- reassessment findings (as indicated)

- date and time of the assessment

- assessment tool used

- pain or comfort indicators present

- description of the patient's behavior

- patient's position of comfort

- patient's activity level

- changes since previous measurements

- pain management interventions performed

- patient's response to those interventions

- progress toward pain management goals

- risk factors for adverse events caused by treatment

- adverse effects of treatment

- name of the practitioner notified (if applicable)

- date and time of notification

- prescribed interventions

- patient's response to those interventions

- teaching provided to the patient and family (if applicable)

- understanding of that teaching

- follow-up teaching needed.